The True Meaning of Tartan Day

The 2020 Tartan Day celebrations were planned with much excitement and anticipation around the 700th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. The months, nay years, of planning could never have prepared us for the circumstances which have now halted these celebrations. From New York City to DC to cities and towns across America, countless Scottish organizations’ plans have been impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. At NTSUSA, we are taking this weekend to reflect and celebrate in a new way with our colleagues and friends at Scots organizations, including the New York National Tartan Week Committee, American-Scottish Foundation, the National Capital Tartan Day Committee, and the Council of Scottish Clans and Associations (COSCA). On Monday, April 6th we hope you will join us in Virtual Tartan Day where the National Tartan Day NY Committee are asking us to flood their social media accounts with videos and photos showing off your Scottish splendor. Visit the Facebook event to learn more about how to participate in virtual Tartan Day.

In the spirit of virtual Tartan Day, we bring you this article The True Meaning of Tartan Day written by John King Bellassai. We hope you find his reflections as fascinating as we did! Many thanks to John for allowing us to share this article with our community.

The True Meaning of Tartan Day

by John King Bellassai*, President of the Council of Scottish Clans & Associations (COSCA) and Vice President of the National Capital Tartan Day Committee.

Soon we American Scots will again be celebrating Tartan Day, with all the hoopla that usually accompanies it. And as always, our cousins back home in Scotland will look on it all with that mixture of bewilderment and amusement that has come to characterize their reaction to our festivities. They are, after all, Scots living in Scotland, and for that reason few of them really understand what all the fuss is about. But Tartan Day is an American holiday, and is not observed as a holiday in Scotland. So it’s really for American Scots to decide what it is all about and how it should be celebrated.

That said, many Americans, too, seem to have missed the point of the Tartan Day holiday. Tartan Day wasn’t meant to be about parades and bagpipes, like most American Scots seem to want to make it—though everybody loves the sound of the pipes and any excuse for a parade is a good one. Nor was Tartan Day intended to be just another opportunity for native Scots to come over here and market their products and services—which is how both the Scottish Government and the Scottish business community always want to approach it, even preferring to call it “Scotland Week”—something which really misses the point and annoys us purists no end. So to cut through all this clutter, it seems useful to write a few lines about the true meaning of Tartan Day—for the edification of readers both Scottish and American.

Statue of Robert the Bruce King of Scots at the site of the Battle of Bannockburn (1314) where Scotland defeated the English armies, preluding the 1320 signing of the Declaration of Arbroath.

Much like Christmas in the modern era, over the past 20 years or so Tartan Day here in the States has become surrounded with glitz and glamour–which in many ways is unfortunate, because it obscures the essentially educational purpose of the holiday, which from the beginning was intended to be all about understanding and celebrating the many contributions made by Scots, and Scottish-Americans, to the founding and building of the United States. That’s what the original resolution, passed by the United States Senate in May of 1998, formally creating the holiday, clearly say it’s all about. And the virtually identical resolution passed by the U.S. House of Representatives, in May of 2005, says the same thing. And there is a great deal there for both Scots and Scottish-Americans to understand and celebrate.

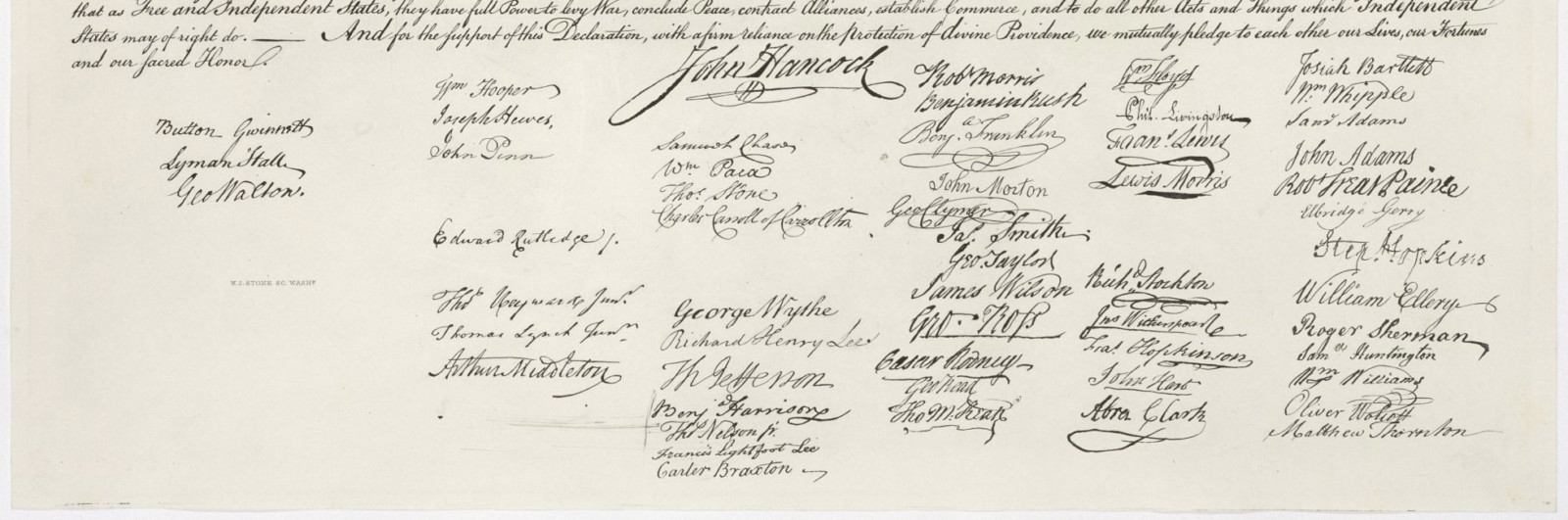

Both congressional resolutions recognize “the monumental achievements and invaluable contributions” made by Scottish immigrants and Americans of Scottish descent to the founding of the Nation—far out of proportion to their numbers in the general population. It is estimated that less than seven percent of the free population of the American colonies on the eve of the Revolution were Scots or the descendants of Scots, yet as a group they played an outsized role in all the events of those times: Both companion bills, Senate Resolution 155 and House Resolution 41, note that almost half of the signers of the American Declaration of Independence in 1776 were of Scottish descent, as were the Governors of nine of the original 13 States, and that these and other Scottish-Americans helped shape the USA in its formative years and guide it through its most troubled times.

American Declaration of Independence, signatures detail

Who exactly were these individuals? And what was the nature of their contributions such that we remember them, and so honor them, to this day? Most readers know about the most of prominent of these—men like James Monroe of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York. Monroe, a third generation Scottish-American, was the fourth President of the United States. (Born in Virginia , Monroe’s paternal great grandfather had emigrated there from Scotland circa 1660. The son of a prosperous planter, Monroe attended the College of William & Mary and studied law under Thomas Jefferson, whose protégé he was.) James Monroe served as Governor of Virginia and later, as American Ambassador to France, where he helped to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Elected President of the United States in 1816 with 80 percent of the popular vote, he was easily reelected in 1820.

Alexander Hamilton was an immigrant to America in 1772 from the island of Nevis, in the British West Indies. The illegitimate son of a Scottish merchant, Hamilton was General Washington’s aide-de-camp during the Revolutionary War and later co-authored the Federalist Papers. He was the founder of the Federalist Party and served as America’s first Secretary of the Treasury. In many ways, he was the architect of the modern American nation-state. (Though we declare ourselves to be a nation built on Jeffersonian principles, in fact we have evolved much more closely to Hamilton’s vision for America—a militarily and economically strong, industrialized nation ,made up mainly of large cities, not of small towns and yeomen farmers.)

Alonzo Chappel, Hamilton's First Meeting with George Washington, 1856. Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library, Lexington, MA

But there were other Scottish-Americans, less well known to history but equally influential, who typify the sort of personages that Tartan Day was designed to remember and honor. Let’s focus on just three of these—all Scottish immigrants to America, each of whom had enormous influence on the other Founders and who helped shape the American Declaration of Independence. They each typify Scottish ethics and values—important parts of our shared cultural and political heritage. These were William Small, who emigrated from Aberdeen to Virginia in 1758; James Wilson, who emigrated from Fife to Pennsylvania in 1765; and the Rev. John Witherspoon, who emigrated from East Lothian to New Jersey in 1768.

Educated at Mariscal College in Aberdeen, Small ended up as Professor of Natural Philosophy at the College of William & Mary in Virginia, where he taught and mentored the young Thomas Jefferson. In his autobiography, Jefferson credited Small with shaping his thinking on the Rights of Man with ideas derived not from London or Paris, but from Aberdeen and Edinburgh, the seats of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Wilson, known in America as “James of Caledonia”, was a delegate to the Continental Congress from Pennsylvania. Equally well read in the works of the Scottish Enlightenment as was William Small, James Wilson was very highly regarded by George Washington, who in his memoires praised Wilson’s abilities and temperament. One of only six men to sign both the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the Constitution in 1789, Wilson was educated at St. Andrews and later taught at the College of Philadelphia, before going on to practice law in America. He contributed greatly to the constitutional debates of the 1780’s which led to the formulation of the modern American tri-partite political system, consisting of co-equal executive, legislative and judicial branches, as embodied in the U.S. Constitution. Wilson was the primary thinker behind the concept of the U.S. Supreme Court. And it was he who convinced Congress to directly state that all powers of government, any government, are ultimately derived from the people—a characteristically Scottish notion.

Statue of John Witherspoon on the Princeton University campus.

But by far the most prominent of these three Scots was the Rev. John Witherspoon, sixth President of the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University. Educated at the Universities of St. Andrews and Edinburgh, Witherspoon was ordained a minister in the Church of Scotland in 1745 and only emigrated to America after actively being urged to do so by Benjamin Rush, who visited Paisley expressly to recruit him behalf of the college. During his 25 years in the job, Witherspoon transformed the small Presbyterian college, founded primarily to train clergymen, into the preeminent university in America. A delegate from New Jersey to the Continental Congress and the only clergyman among them, Witherspoon actively served on over 100 committees and was the most outspoken among the delegates on behalf of full political separation from Britain. He not only himself signed the Declaration of Independence, but in the decade preceding it, educated many of the first generation of political leaders in the new United States of America.

Throughout his academic career, Witherspoon was an eloquent and outspoken proponent of the Common Sense Philosophy espoused by the Scottish Enlightenment scholars Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, Thomas Reid, Lord Kames, and others, which he taught at Princeton. From among his students came 12 other members of the Continental Congress, each of whom signed the Declaration of Independence, plus one American President (James Madison), one American Vice President (Aaron Burr), 37 judges (three of whom later became U.S. Supreme Court justices), 28 U.S. senators, and 49 U.S. congressmen.

President John Adams once said of Witherspoon, “I know of no character, alive or dead, who has done more real good for America.” A bronze statue of Witherspoon, by Scottish Sculptor Alexander Stoddardt, stands on the campus of Princeton University, and an identical twin to it stands outside the University of the West of Scotland, in Paisley. Yet another stands in downtown Washington, DC near the busy intersection of Connecticut Avenue and 18th Street, NW.

* John King Bellassai is President of the Council of Scottish Clans & Associations (COSCA) and Vice President of the National Capital Tartan Day Committee. (His maternal grandfather, John King, after whom he is named, emigrated from Killearn, in Stirlingshire, to America in 1910.)

We leave you this 2020 Tartan Day with a close up of one of our favorite tartan clad Highlanders – William Gordon of Fyvie by Pompeo Batoni.

See you all for Tartan Day in 2021!