Secrets of a Shrine (Part II)

Hamilton’s design for the Alloway monument is in two parts, allowing him to meet the brief of commemorating Burns’ ‘birth and genius’.

Robert Burns Monument. David Ross Photography.

The base is a three-sided prism of coarse Garscube sandstone. The three sides face the three ancient regions of Ayrshire: Kyle, Carrick and Cunninghame. Niches in the stout walls and a cella (chamber) within were intended to hold likenesses of the poet. This base grounds Burns in his native soil, reminding us of his birth and mortality.

The superstructure is made from durable sandstone, quarried at Cullalo in Fife. It’s surmounted by an elaborate finial, supported by three dolphins made from local sandstone, and a copper gilt tripod. These features symbolise Apollo, the Greek god of poetry. Apollo presided over the nine muses, who are represented by the nine columns of Burns Monument, and his laurel branch motif and signature lyre appear in and around the cupola. The muses were created to give inspiration, knowledge, artistry and music to the ancient world. These allusions to classical antiquity and immortality were intended to convey Burns’s genius; the building appears to be saying: ‘Burns was from here but through his life and his genius he’s earned a place with the gods.’

The proportions of the Alloway monument provide a clue to other secrets in the design. In sharp contrast to the low-lying birthplace cottage, this was a tall structure visible from afar. The monument’s height divided by its breadth produces the figure 1.618. This number, known as the golden mean or golden ratio, has long been considered the perfect proportion and is found in the length of the hand and the forearm, or at the Great Pyramids of Giza. This aesthetic, along with the classical design and the repetition of the number three in almost every aspect of the building’s design, would have been understood by another community of interest: freemasons.

Burns Monument is a tribute to a freemason by freemasons. Like Burns, Hamilton and the founding trustees were all freemasons. The foundation stone, including a time capsule with full masonic orders, was laid on the poet’s birthday in 1820. The whole structure symbolises the progress of an apprentice mason to master mason: moving from the doorway and basement (entered apprentice), to the winding stair from the basement to the parapet (fellow of the craft), and to the parapet itself (master mason).

The winding staircase, now showing signs of damage

Freemasons believe that odd numbers are perfect and represent the divine. If one represents man, and two woman, three is their union. The number three is repeated in the number of steps (27, or 3 x 3 x 3), the triglyphs (tablets with three vertical grooves) inside the monument, three panelled doors, the shape of the base, and so on. An odd number also means that the foot used to begin the ascent is not the foot used to complete it, echoing the transformation that comes about through learning.

The stairs convey you to the upper level of the monument or the ‘sanctuary of truth’ but their winding nature means you cannot see your destination, another metaphor for the experience of learning. We require the help of the liberal arts (rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, etc) and our senses, to move through degrees of sophistication; on the monument, the order of capitals gets more decorative as they go up: Doric or plain in the basement to Corinthian in the nine pillars above. It remains a mystery why Hamilton did not follow the masonic tradition of a clockwise turn of the stairs, mimicking the movement of the Earth around the sun.

Another theme evident throughout the structure is mortality/immortality. Since prehistoric times, circles and domes have been thought to represent the shape of the human head, the cosmos, and a being without beginning or end. The double dome in Burns Monument is embellished with Greek key or meander motifs, geometric representations of the river in modern-day Turkey whose long, snaking course connotes eternity. Bulls were the traditional offering to Apollo (oxen were sacrificed to Jupiter) – they would have been brought garlanded to the temple, and their skulls were displayed after sacrifice. Bucrania, or bull skulls, are found around the central lantern of Burns Monument and are a reminder of both the mortality and the new status of Burns as one for whom sacrifices are made.

Bucrania on Burns Monument

Less than a decade after the opening of Burns Monument in 1823 came the first artifacts. Statuary was always intended for the building but the first statues were not of Burns. Life-size sandstone figures of Tam o’ Shanter, Souter Johnnie and Nanse Tinnock (a Mauchline innkeeper), carved by local monumental mason James Thom, were hugely popular with Victorian audiences who admired the sort of detail missing from the Dumfries Turnerelli frieze. From the proceeds of a British tour, a stone pavilion was built for the statues a short distance from Burns Monument, considered a more fitting venue for such carousing characters than the austere, sober monument. In agreeing to accommodate the statues Burns Monument Trust was staying true to its mission to honor ‘the birth and genius’ of Burns as well as responding to a public demand for what Nicola Watson terms ‘text-free tourism’ (The Literary Tourist, 2006). They had become collectors of how other people chose to remember Burns.

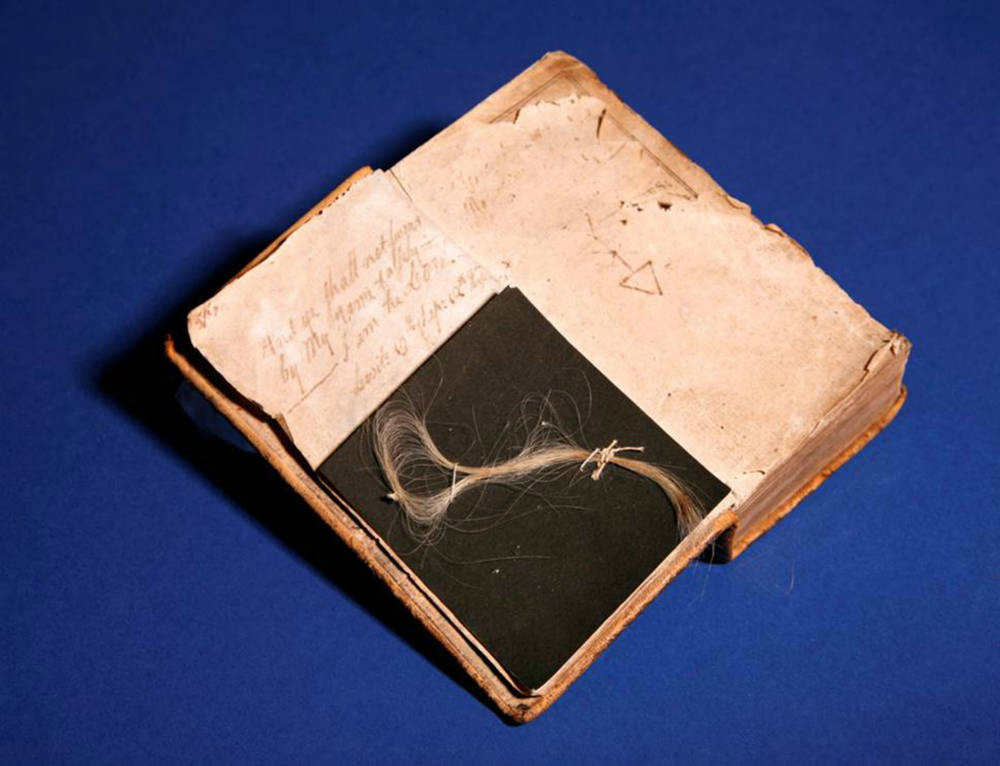

The ‘Highland Mary’ bible at Robert Burns Birthplace Museum

The first artifact to be displayed inside Burns Monument came eight years later: a bible in two volumes with inscriptions by Burns and a lock of hair reputed to have belonged to his lover ‘Highland’ Mary or Margaret Campbell. This was gifted to Burns Monument Trust by admirers of the poet in Montreal. The books carry his masonic mark and oaths written in the fly leaf. This object signified another departure from the original intentions of the Trust – it had little to do with the birth or genius of Burns but made a claim that his private life was in the public interest. Indeed, the Trust would come to display the artifact beside the wedding ring of Burns’s wife.

It’s also significant that the first artifact intended for the monument was corporeal. The lock of Campbell’s hair attached to the bible, as well as writing in the poet’s hand, suggest that the physical presence of Burns was needed. This material indicates a move away from the classic memorializing of Burns in favor of what visitors to the monument, who came in their hundreds of thousands, might consider more familiar and relatable.

Written by David Hopes, Head of Collections and Interiors (Policy), National Trust for Scotland