Secrets of a Shrine (Part I)

Alloway’s magnificent monument to Robert Burns opened 27 years after the death of the poet, and it continues to yield secrets about the movement to build it and the meaning behind its design.

A project is underway to conserve and reinterpret Burns Monument, so we’ve taken a good look at its origins, construction and early use to help us with what is needed to repair the building, using 200-year-old clues buried deep in the archive of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum.

The death of Robert Burns in 1796 set in train efforts across the world to memorialize Burns. Burns had been laid to rest yards from his last home in the town of Dumfries, in a grave which was unremarkable given his celebrity and fame. In 1815, subscriptions were gathered by former friends to fund a more fitting memorial. Two years later, the body of Burns was exhumed, casts were made of his skull for phrenological analysis, and he was re-interred in a specially-designed mausoleum in the same graveyard. This movement prompted Burns admirers in the place of his birth, 50 miles away in Alloway, to get in on the act.

Burns Mausoleum in Dumfries.

There were four elements of the Dumfries campaign which would prove influential in the monument that was eventually built at Alloway:

Giving Burns a separate burial place (later painted brilliant white), in what was a crowded graveyard of browning sandstone masonry, made a strong statement about his importance. This was a grave visible from a distance, as can be seen in an early watercolour of the mausoleum. Burns was different from other mortals and he was to be remembered as such.

Alloway took note of the design of the Dumfries mausoleum. Despite his fondness for Tudor architecture, architect Thomas Frederick Hunt (1791–1831) had chosen the Greek Revival style that was popular at the time. It was an appropriate style for remembering a poet in classical tradition, but the sober style might also have been a way of rehabilitating the memory of a fallen man. The circumstances of the poet’s death had been speculated upon by the sententious Reverend James Currie whose biography of 1800 had done much to dent Burns’s reputation.

The theme of the Dumfries mausoleum would also express itself in the Alloway monument. The poet’s muse, his source of inspiration, had been celebrated and encoded by Burns in his own work and he had been delighted with the epithet ‘heav’n taught ploughman’ given to him in an influential review of his first book. For his early admirers this ‘muse’ explained how someone from such a humble background could craft works of such sublimity and how he was ‘chosen’ among men. This was an ideal theme for a memory site, combining the mortal Burns and his immortal calling.

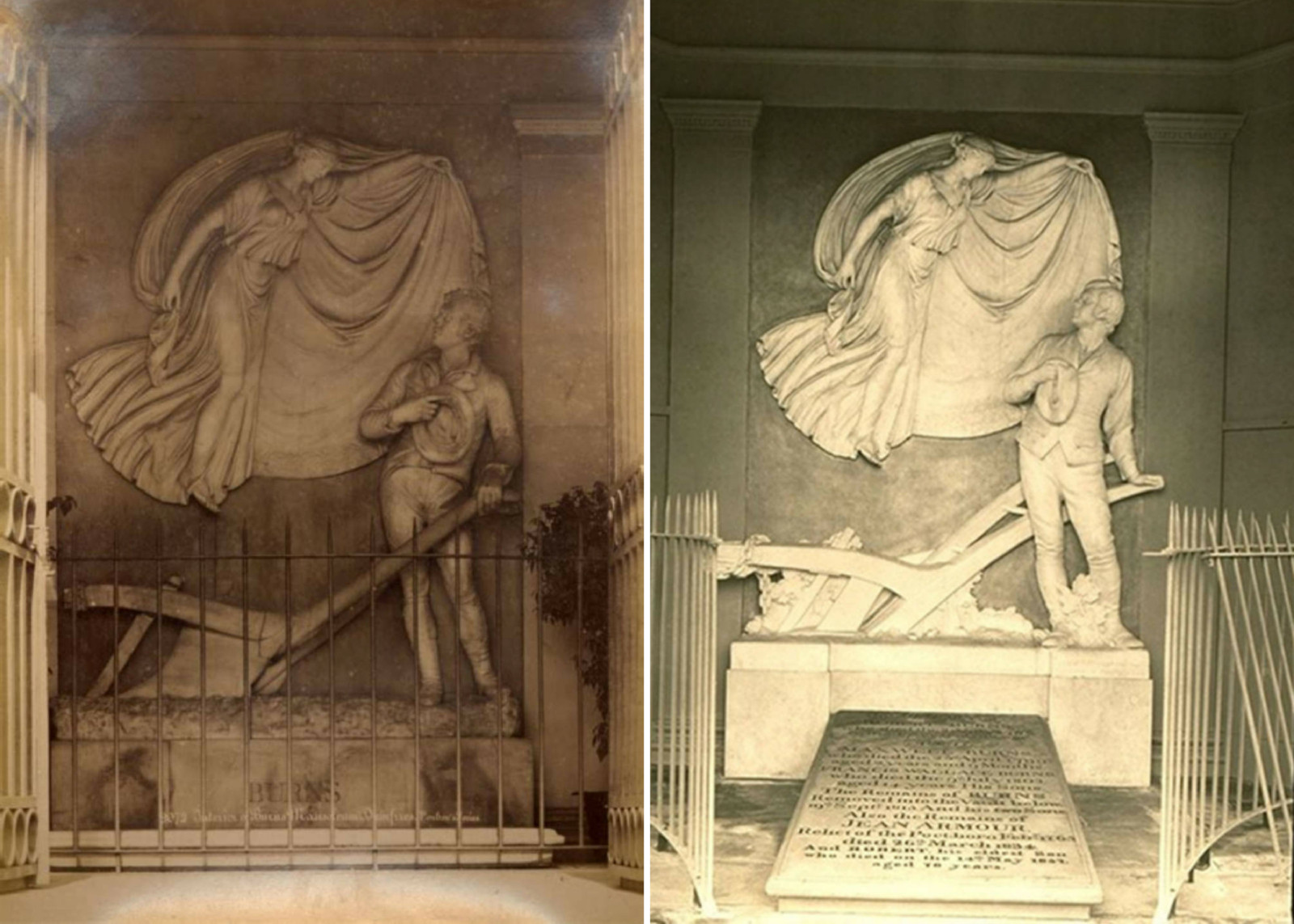

Left: The early sculpture. This shows Turnerelli’s classic depiction of Burns ploughing the field. Right: The amended sculpture. The amendments to Burns’s clothes and the plough can be clearly seen here. Note also that there is no longer a closed barrier between the visitor and the sculpture.

The Dumfries campaign to remember Burns was a collective effort but there was disagreement over the manner of memorialization. On the left is the original marble sculpture featuring Burns apprehended at the plough by Coila, his spirit muse. It’s a romantic theme classically executed. However, the sculptor Peter Turnerelli (1772–1839) was criticized for being too allegorical in his handling of the subject and not true enough to the detail of, for example, Burns’s clothing and the type of plough. Such was the strength of grassroots resistance that adaptations (right) were made by Joseph Hermon Cawthra in 1936. Burns’s memory was pulled between high society classicization on one hand and popular romanticism on the other; this would recur in the Alloway monument.

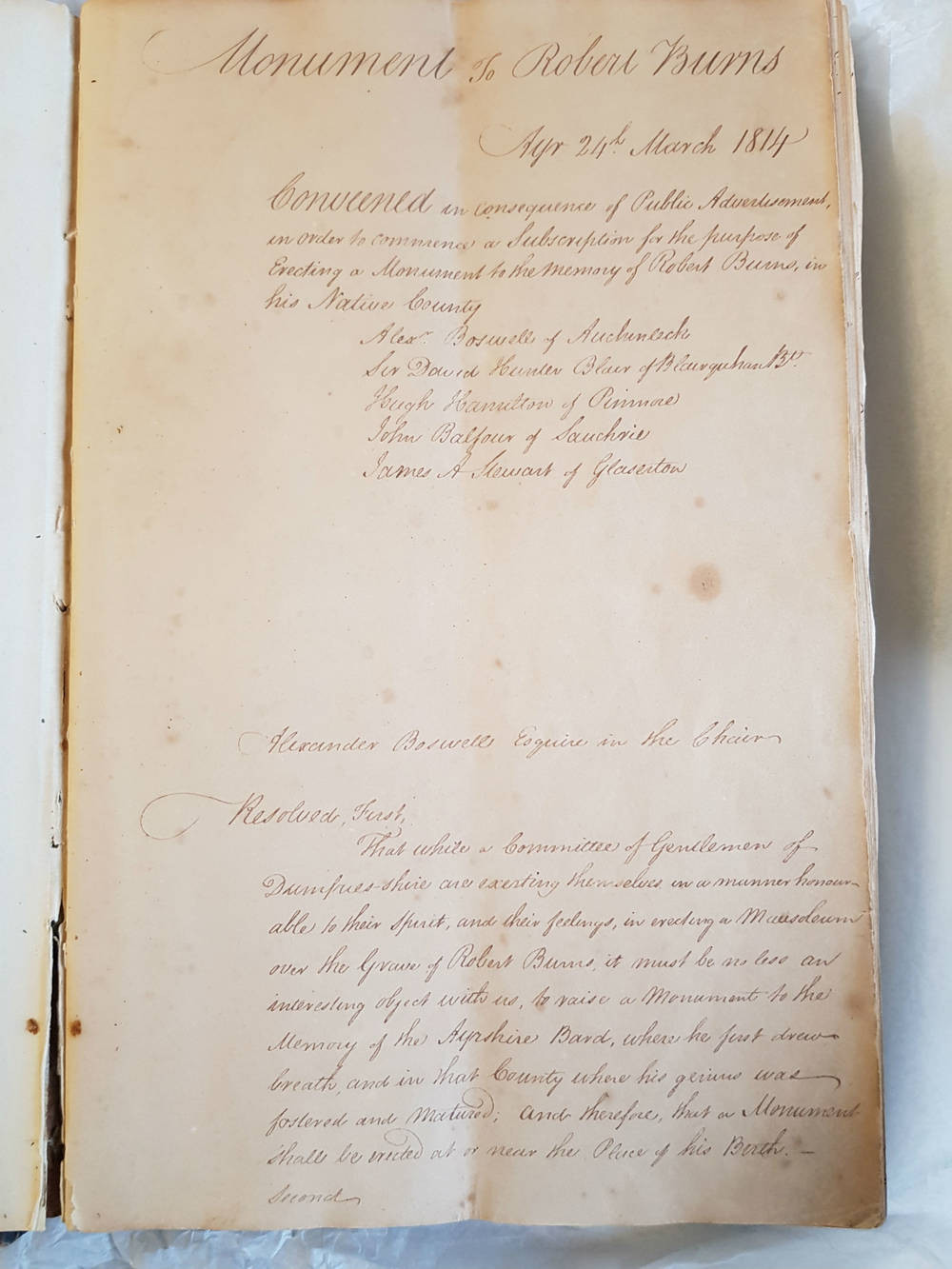

Inspired by Dumfries, five gentlemen from Ayrshire, some of whom knew Burns, formed a committee, chaired by Alexander Boswell of Auchinleck (son of the diarist James Boswell), to create a suitable commemoration of Burns in Alloway. An excerpt from the first minute of Burns Monument Trust is kept in Robert Burns Birthplace Museum:

The minute from the first meeting of Burns Monument Trust.

‘That while a committee of Gentlemen of Dumfries-shire are exerting themselves in a manner honourable to their spirit, and their feelings, in erecting a Mausoleum over the Grave of Robert Burns, it must be no less an interesting object with us, to raise a Monument to the memory of the Ayrshire Bard, where he first drew breath, and in that County where his genius was fostered and Matured; and therefore, that a Monument shall be erected at or near the Place of his Birth. That for this purpose, a Subscription shall be immediately set on foot, and as there can be little doubt of the anxiety of all ranks to offer tribute to the memory of Burns, it is the opinion of this meeting, that no individual should be debarred that gratification.’

We can see from Boswell’s language that there was a sense of rivalry with Dumfries-shire but Alloway would be set apart in its mission to remember ‘birth and genius’ in Burns’s native county.

Burns Monument Trust considered various sites in Alloway, including Burns Cottage. In 1814 the cottage was owned by the Incorporation of Shoemakers of Ayr and run as a tavern. Negotiations did not progress and the Trust instead looked to another site, owned by David Cathcart, Lord Alloway (1764–1829) near two other landmarks esteemed by Burns lovers: Alloway Auld Kirk and Brig o’ Doon. In 1819, one rood (about a quarter acre) of land was secured on an elevated site above the River Doon. Sanctified in song by Burns and notionally sited on Tam o’ Shanter’s escape route, this was a prominent, romantic spot from which one could view the ‘land o’ Burns’.

In 1818, Thomas Hamilton Junior (1784–1858) was appointed to design a suitable structure. Burns Monument established Hamilton’s reputation as one of Scotland’s foremost Greek Revival architects. He went on to design the Burns Monument on Calton Hill and the Dean Orphanage (now the Gallery of Modern Art) in Edinburgh, the town hall and Wallace Tower (1831) in Ayr, and the John Knox monument in the Glasgow Necropolis. The choice of architect revealed a class divide in the Alloway movement: Burns Monument Trust wanted to show themselves as arbiters of taste but this was not altogether popular with the grassroots Burns movement.

Monument of Lysicrates, Athens

So where did Hamilton get his inspiration?

Undoubtedly he was influenced by the Dumfries mausoleum but there were other precedents. One of the main architectural influences was the Monument of Lysicrates in Athens (335/334 BC), the earliest surviving example of Corinthian capitals. Hamilton would have seen this building in Stuart and Revett’s Antiquities of Athens (1755), a book that popularised Greek architecture following a period of isolation during the Ottoman occupation. Lysicrates was a wealthy patron of the arts who wanted to commemorate artistic achievement.

In choosing this design, Hamilton was suggesting that Burns Monument Trust was acting in a similar role. The Monument of Lysicrates is positioned in Plaka on an old processional route to the Theatre of Dionysus on the Acropolis. A frieze around the top shows scenes from the life of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and excess. The Alloway monument is positioned on the route of Tam o’ Shanter’s journey home, himself a worshipper of Dionysus. This would not have been missed by those with a classical education and knowledge of Burns.

Hamilton might also have been aware of a painting said to have been owned by the artist Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1820). Burns at the Plough (1800) by Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759–1817) depicts Burns looking at a field mouse, bathed in heavenly light issuing from a circular temple resembling Nasmyth’s own St Bernard’s Well in Edinburgh. Indeed there is a long tradition of circular temples being used to remember poets; in the case of Burns Monument the design of a structure which was at once enclosed and open to the elements might have been considered appropriate for a nature poet and was certainly repeated in subsequent memorials (as seen at Ingram’s Burns Monument in Kilmarnock, 1879).

‘Burns at the Plough’ by Julius Caesar Ibbetson.