Mr. and Mrs. Mackintosh

When you think of Glasgow many things may come to mind – rain, chips, deep fried chocolate, and of course Charles Rennie Mackintosh. His style and influence can be seen across the city, including the “Welcome to Glasgow” snapchat filter!

It presents the question, however, what inspired such an influential and iconic man? Mackintosh would likely be the first to credit his wife and longtime collaborator, Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh, for her vast influence on his work.

You must remember that in all my architectural efforts you have been half if not three quarters in them.

– Letter from Charles Rennie Mackintosh to Margaret; May 16, 1927

“The Glasgow Girls”

Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh

Margaret MacDonald is recognized not only for her artistic influence on Mackintosh but the arts across turn-of-the-century Britain. She experimented with and mastered a variety of media including watercolor, metalwork, embroidery, and textiles – but probably most notable was her use of gesso. Margaret was born in 1864, and was settled in Glasgow by around 1890. Margaret and her younger sister, Frances, shared a passion and talent for art. Soon after their move to the city, both sisters enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art in the premier co-ed class for the institution at a time when female artists were flourishing. Students at GSA formed groups like the Glasgow Society of Lady Artists whose mission was to advocate for women’s suffrage and seek equal recognition as men for their artworks. “The Glasgow Girls” as they would later be known, were the most active and influential of these women which included the two MacDonald sisters, Jessie Newbery, Ann Macbeth, and Jessie M. King, to name a few. The Glasgow Girls and their peers would develop the iconic “Glasgow Style” that permeates design, fine arts, and architecture.

“The Glasgow Four”

Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his closest friend Herbert McNair, both students at the school, were introduced to Margaret and Frances MacDonald by Francis Newbery, Head of Glasgow School of Art. He anticipated a collaboration would be a successful opportunity for all parties to showcase their work which complimented one another so well. Charles, Herbert, Margaret and Frances indeed collaborated well and were quickly christened as “The Four”. The collaboration lasted several years and became a cultural driving force not only at the Glasgow School of Art but across Europe. Preceding Art Nouveau, which has its roots in turn-of-the-century Vienna, it can be argued the revolutionary Art Nouveau movement found its influence in the artistic ingenuity of the Glaswegians. Romance among “The Four” blossomed and Charles and Margaret soon became a couple, as did Frances and Herbert.

Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections

A Marriage Literally and Figuratively of Two Artists

The success of their collaborative style lead Mackintosh and Margaret to work closely on several interiors including 120 Mains Street (1900), the couple’s first marital home, and a commission from Miss Catherine Cranston, a pioneer of the highly fashionable Glasgow tea room. In the late 19th and early 20th-century, tea rooms were the meeting place for high society. This very public commission became the first iconic example of their combined style, culminating in the Room de Luxe at Miss Cranston’s Willow Tea Rooms. Other collaborative commissions of the time were designs for the House for an Art Lover (1901) and The Rose Boudoir at the International Exhibit at Turin (1902). Margaret provided drawings and decorative gesso panels for each interior. Margaret’s influence in these early years is critical to the stunning union the couple ultimately create between architecture and design.

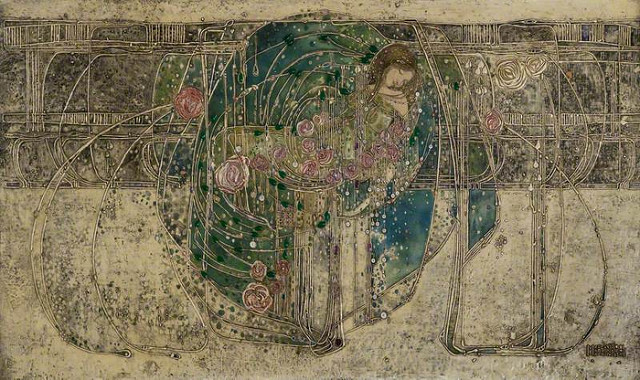

“Sleeping Princess” gesso at The Hill House by Margaret MacDonald

The Hill House: A Fairytale by Design

This brings us to the National Trust for Scotland property, The Hill House. In the same year as designing the Room de Luxe at the Willow Tea Rooms, the very busy pair were commissioned by Walter Blackie to design his family home in Helensburgh, just west of Glasgow, atop a hill overlooking the Firth of Clyde. Everything was to be designed by the artists, even the cutlery! For the interiors, Margaret took inspiration from the Blackie family – who had made their living from publishing fairytales. Together, Margaret and Mackintosh created a masterpiece. The entrance hall feels as if you are walking right into the enchanted woods; the drawing room takes your imagination into an elegant rose garden with its extraordinary “Sleeping Princess” gesso above the mantle; and in the bedroom, embroidered silk panels of dreaming women flank the white carved bed and rose colored glass panels. The exterior of The Hill House is striking in its unornamented simplicity. Abstract shapes and forms assemble and reassemble at different angles and points of view. Mackintosh’s approach to the exterior contrasts to the organic nature of the interior, creating a barrier from one world to another.

This brings us to the National Trust for Scotland property, The Hill House. In the same year as designing the Room de Luxe at the Willow Tea Rooms, the very busy pair were commissioned by Walter Blackie to design his family home in Helensburgh, just west of Glasgow, atop a hill overlooking the Firth of Clyde. Everything was to be designed by the artists, even the cutlery! For the interiors, Margaret took inspiration from the Blackie family – who had made their living from publishing fairytales. Together, Margaret and Mackintosh created a masterpiece. The entrance hall feels as if you are walking right into the enchanted woods; the drawing room takes your imagination into an elegant rose garden with its extraordinary “Sleeping Princess” gesso above the mantle; and in the bedroom, embroidered silk panels of dreaming women flank the white carved bed and rose colored glass panels. The exterior of The Hill House is striking in its unornamented simplicity. Abstract shapes and forms assemble and reassemble at different angles and points of view. Mackintosh’s approach to the exterior contrasts to the organic nature of the interior, creating a barrier from one world to another.

The Transformative Materials of The Hill House

To achieve an unornamented façade, Charles Rennie Mackintosh clad The Hill House in what was at the time considered state-of-the-art building material: Portland cement. The unfortunate result has been persistent and increasingly damaging water penetration that places the house and its artful interiors at severe risk of falling roughcast, damp, and dry rot. Remedies attempted over the past six decades have had an adverse impact on the house’s condition. Seeking a reliable solution, the National Trust for Scotland has embarked on a multi-year project that will result in a long-term maintenance and repair methodology as well as the conservation of the building’s exterior in full view of the public so that visitors can experience firsthand the painstaking, groundbreaking work that goes into preserving an irreplaceable piece of architectural history.

To achieve an unornamented façade, Charles Rennie Mackintosh clad The Hill House in what was at the time considered state-of-the-art building material: Portland cement. The unfortunate result has been persistent and increasingly damaging water penetration that places the house and its artful interiors at severe risk of falling roughcast, damp, and dry rot. Remedies attempted over the past six decades have had an adverse impact on the house’s condition. Seeking a reliable solution, the National Trust for Scotland has embarked on a multi-year project that will result in a long-term maintenance and repair methodology as well as the conservation of the building’s exterior in full view of the public so that visitors can experience firsthand the painstaking, groundbreaking work that goes into preserving an irreplaceable piece of architectural history.

Learn more about the campaign to save one of the world’s most iconic and celebrated houses.