Let’s play a game …

This educational musical game from 1801 was the first of its kind, and is one of very few known to still be in existence.

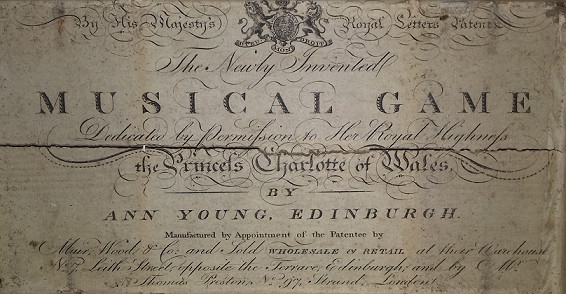

In 1801, Ann Young of Edinburgh obtained a patent from George III for an educational children’s musical game. She was the only woman to receive a patent in 1801, and one of just 40 women to obtain a patent in the 200 years between 1617 and 1816. Here we see the label, attached to the game, which confirms Ann Young’s patent.

Ann was a performer and teacher during Scotland’s Enlightenment. Alongside teaching ladies the clavier, harpsichord and pianoforte, she produced musical instruction manuals, such as Elements of Music and of Fingering the Harpsichord (c1790) and An Introduction to Music (1803). At the time Ann patented her game, she lived in St James Square in Edinburgh. As well as being home to Robert Burns at one time, St James Square was at the opposite end of George Street to Charlotte Square, where the Lamont family lived at No. 7 – now the National Trust for Scotland’s Georgian House. The Lamonts were the first owners of the house and the Trust has restored it to this period.

In 1801–03, Ann invented an ‘amusing and interesting’ game to teach and test musical theory. It was designed to teach children as young as eight, and the players could choose one of several versions to play, depending on their ability. It was a family-friendly game, and certainly something the Lamont family might have owned.

Musical instruction was very popular among the wealthy elite in Great Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries. For ladies especially, it was a necessary accomplishment. The performance, appreciation and knowledge of music were part of the education of both girls and boys, and were an indicator of social status. The complexity of this game demonstrates the high level of tuition in music received by children, and that proficiency in it was a prized skill.

Her musical game was actually six games in one, described as an:

‘improving exercise … in the fundamental principles of the science of Music, particularly all the keys or modulations, major and minor, common and uncommon signatures, musical intervals, chords, discords with their resolutions, and the most useful rules of thorough bass’

From a 21st-century perspective, this game is not for the faint-hearted! It requires a strong understanding of keyboard anatomy before play even commences. The instructions refer to players as ‘performers’ and require a keyboard to be nearby.

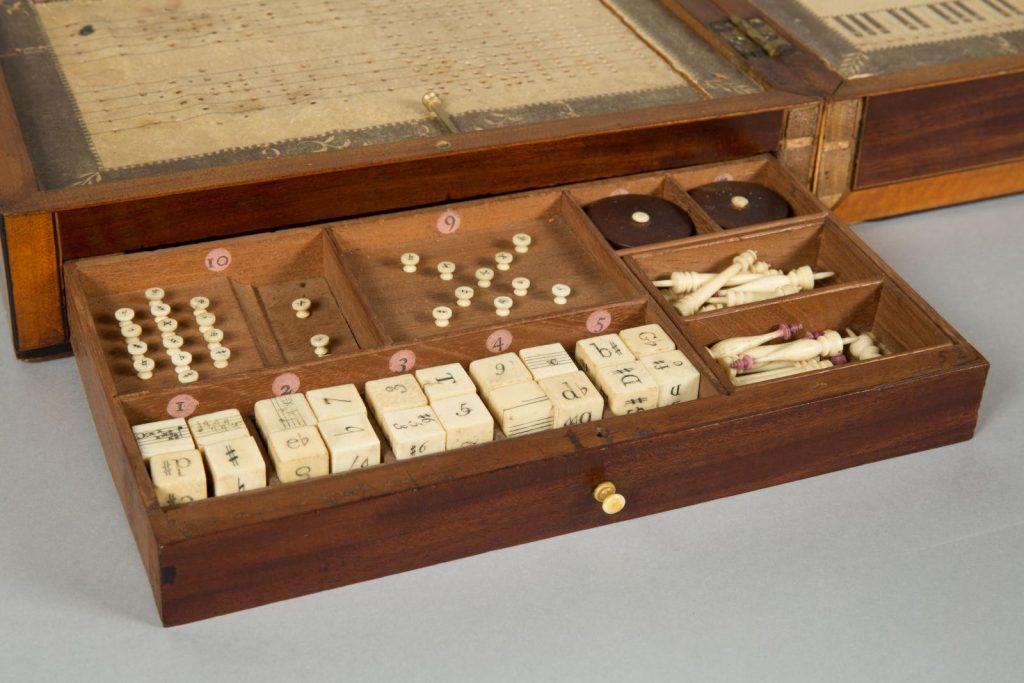

One of the drawers of Ann’s game open, showing some of the pieces

The game itself is presented in a mahogany, satinwood-banded and ebony-lined box, which when opened reveals a playing board. The board is comprised of two inserts with keyboards, staves and leger lines printed on one side, and a magnified stave on the other. Both inserts have small holes in which turned bone and ebony pins are placed. There are drawers on either side of the box containing the finely made pins, dice and counters used to play the game.

The dice are particularly intricately decorated with musical symbols, including key signatures, clefs and single letters. These could be used interchangeably depending on which version of the game was being played.

Very few of these games have survived – one is on display at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, one is at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and one is held by the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. We can now add this example to the list, and be proud it has a home in the city in which it was designed and made.

Project Reveal

This article is by Rachael Bowen, Christophe Brogliolo, and Ben Reiss of Project Reveal Team East. Project Reveal is a multi-site digitization project of unprecedented scale. With your support, we can help the Trust manage its collections more effectively. Most important, we can help the Trust discover, better understand, and share its treasures with the world.

Please help us to secure this major investment in preserving Scotland’s heritage with a tax-deductible donation in support of Project Reveal.

This article was originally published by the National Trust for Scotland on February 8, 2018.